All good analysis looks at both sides of a situation. Fixating on one side because of bias or convenience can lead to disastrous outcomes. Today, I’m going to try to give the opposing view to the inflationary commentary I highlighted in last week’s post.

Importantly, I highlighted that rates may be moving higher for reasons in addition to higher inflation. That said, this week commentary and actions from global central banks, including the Federal Reserve has pushed rates down rather dramatically (down 7% since Monday). This is not normal interest rate behavior. As I mentioned last week, rate volatility is at all-time highs in 2022, at least going back to 1871.

Recession

Many participants in the investment community are anticipating a recession and believe rates will decline, pushing bond prices higher. We have observed softening in several areas of the economy but still haven’t arrived at full-blown recession levels yet in all pockets.

Housing Market

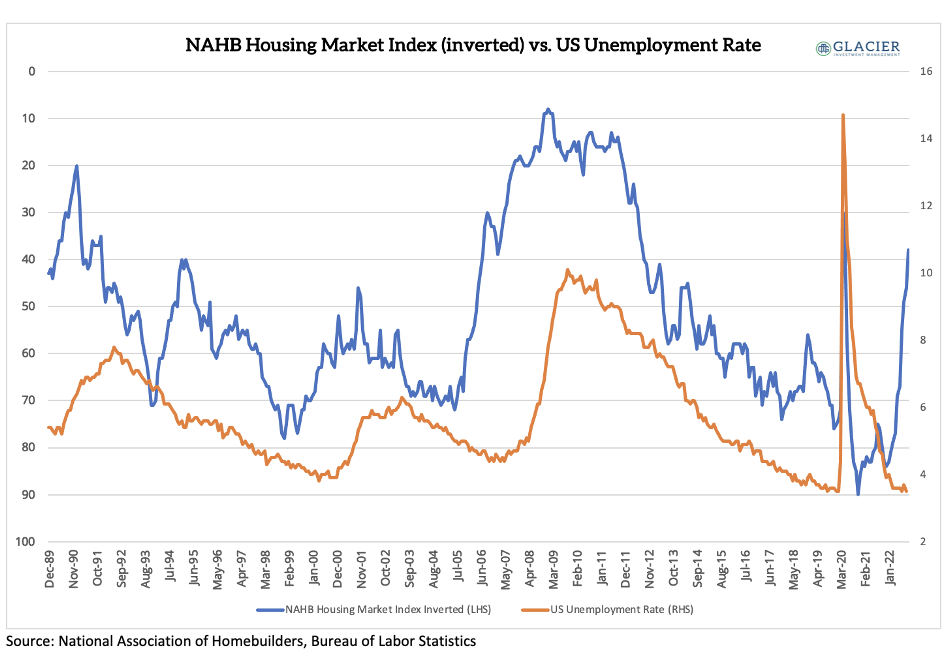

One major area of concern is the housing market. I’ve discussed this with several of you during our reviews this month. I came across the chart below, courtesy of Alf at the Macro Compass.

The blue line is the National Association of Homebuilders US housing index, which measures sentiment in single family housing market based on market conditions for the sale of new homes at the present time and in the next six months as well as traffic of prospective buyers of new homes. The blue line is inverted, meaning higher sentiment is lower on the y-axis and lower sentiment is higher on the y-axis.

The orange line is the unemployment rate in the US., which as you can see goes down when the NAHB index is going up and goes up when the NAHB index is going down. As a result, I would expect unemployment to meaningfully increase in 2023. Given the housing market is such an integral component of our economy, a recession in 2023 appears to be fairly likely. The severity of any recession is difficult to predict, but a recession doesn’t mean our inflation problem is solved.

Declining inflation

Inflation has historically declined during a recession, which I would anticipate occurring in the next recession. In a recession, demand typically declines substantially while supply takes time to respond, leading to lower price growth (inflation). Over the typical business cycle, inflation declines into, through, or even after a recession followed by a recovery in demand which eventually pushes inflation back up and so it ebbs and flows with the business cycle. Inflation usually doesn’t stay down after a recession with the glaring exception being the period from 2010 to 2019.

Sticky Inflation

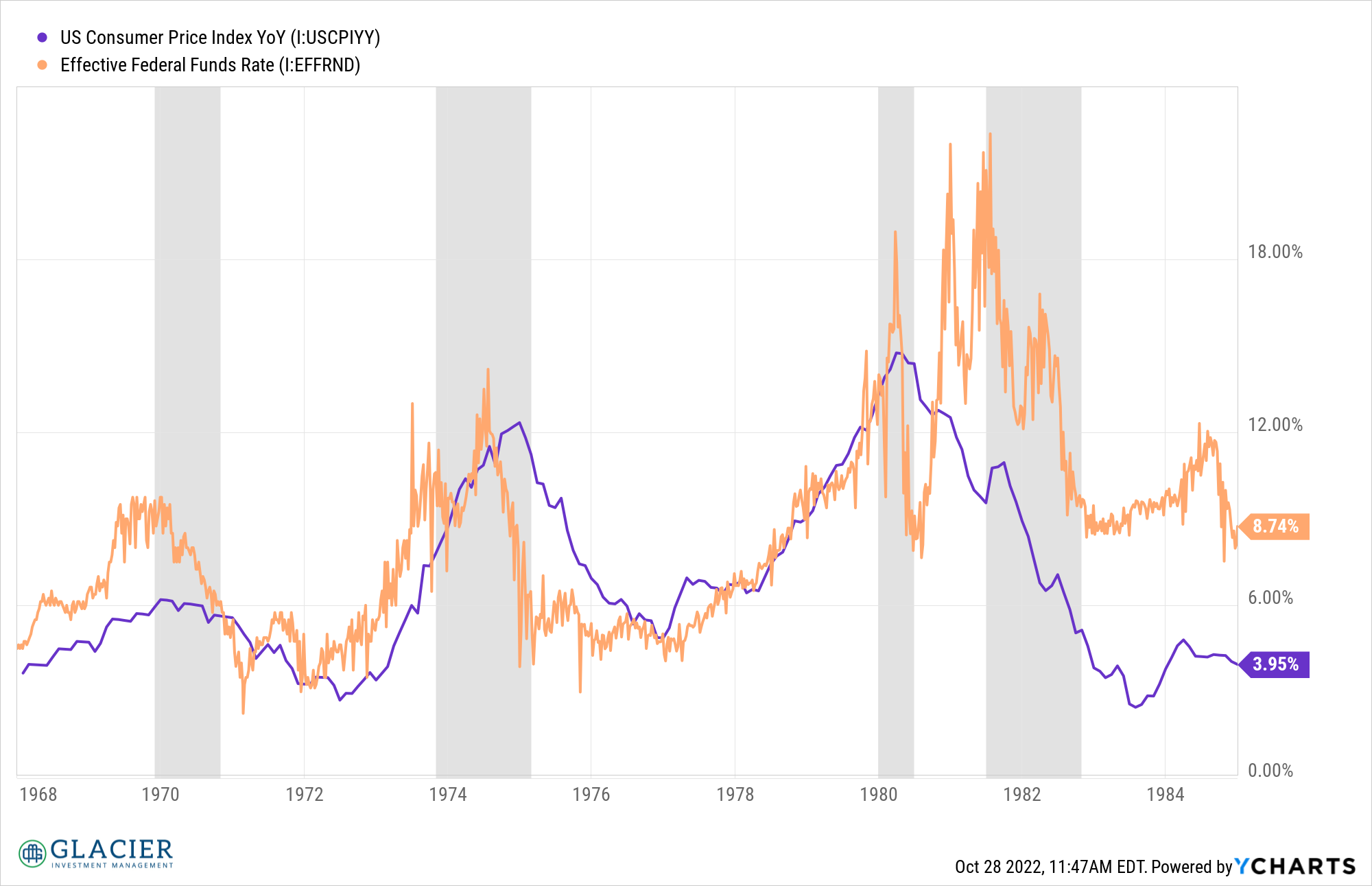

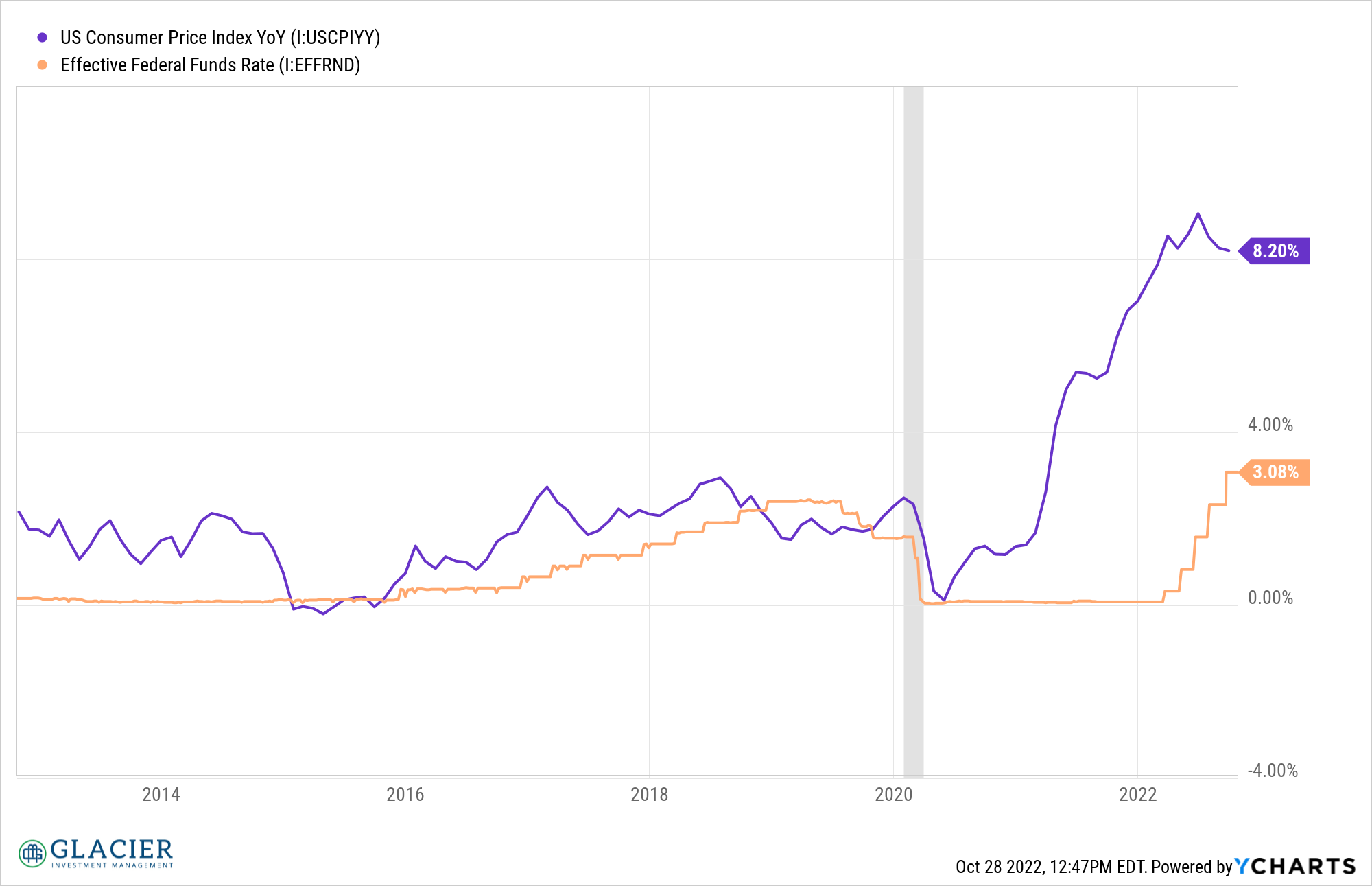

The US economy has gone through periods where inflation was sticky and wasn’t in an acceptable range for policy makers, or the general public for that matter. In the chart below, we see the consumer price index (CPI, purple line) reached a peak of just over 12% in the 1973-1974 recession and subsequently declined to just below 5% only to rise again to almost 15% in the 1980 recession.

The orange line is the effective Fed Funds rate. As a reminder, the Federal Reserve sets a target Fed Funds rate that banks use to lend to other banks. The effective rate is the weighted average of the actual rates charged by banks.

What’s important to note about this chart is where the Fed Funds rate was in relation to CPI in the 1970s. Notice how this rate spent most of the decade above the year-over-year CPI readings. It wasn’t until the Fed Funds rate was well above CPI (10-13% above!) for a good 16-18 months that the sticky inflation trend finally broke.

No two periods in history are exactly the same but as has been attributed to Mark Twain, history does rhyme.

So which is it?

Right now for disinflation/deflation to return, one of the following needs to occur:

- A recession, although that won’t necessarily break a sticky inflation trend.

- A cataclysmic deflationary shock (think the Great Financial Crisis or the Great Depression).

- The disruptions from the global pandemic and geopolitical shocks “normalize” and we return to the pre-2020 “normal”. I think there are several reasons why this won’t happen. Between higher energy costs due to lower supply from lack of investment and regulation, a different labor force composition, and shifting globalization trends it feels like we’re in a higher price era for at least the next several years.

- There may be other catalysts not captured by numbers 1-3 above.

Anything is possible in the world we live, but it’s awfully difficult to predict and handicap major crises, let alone when they will occur. We need to operate with the information we have and reasonable probabilities. Importantly, a “crisis” doesn’t have to be deflationary. It could be inflationary.

As I mentioned last week, war is inflationary. Both hot and cold wars are happening all around the world. A potential financial crisis being increasingly discussed is a global sovereign debt crisis. Governments have too much debt and interest rates can only go so high before negatively impacting the solvency of the borrowing governments (see the UK a few weeks ago). If inflation is indeed sticky and central banks can’t raise rates high enough for long enough, elevated inflation trends may not be able to be broken.

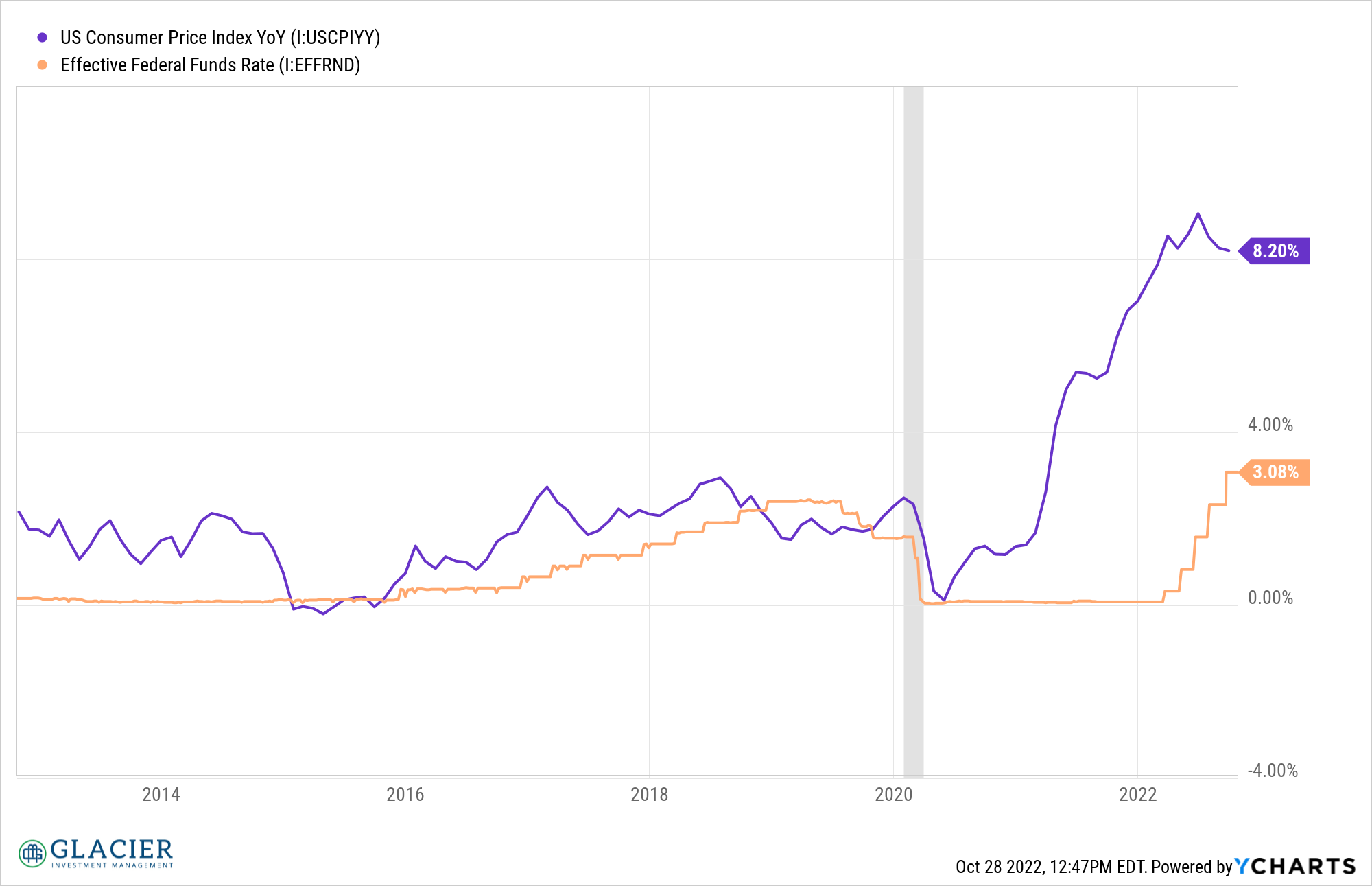

Today, the effective Fed Funds rate is at 3.08% while the most recent headline CPI figure was at 8.20%. If we’re using the 1970s as a guidepost, Fed Funds would need to be materially higher to break a sticky inflation trend.

As you can probably tell, I’m leaning towards the inflation scenario being more likely over the next five years than the disinflation/deflation scenario. I think a recession is likely to occur in 2023, but it isn’t a sure thing. If a recession doesn’t occur, then any inflation relief may be fleeting. If inflation doesn’t prove to be sticky, then rates will likely settle down, leading to improved bond performance.